In the ongoing fight for inclusive communication, we find ourselves in a moment that echoes the past. Decades ago, American Sign Language (ASL) struggled to be recognized as a legitimate language. Today, we’re seeing a similar journey unfold for non-speakers who rely on letter boards and other forms of alternative communication in classrooms. These tools, which honor the principle of presuming competence, are reshaping what’s possible for non-speakers—just as ASL did for the Deaf community. Looking back on ASL’s journey not only illuminates the struggles and biases that these communities have faced but also points the way forward in our fight for the rights of non-speakers to communicate on their own terms.

The Journey of ASL: A Story of Stigma and Advocacy

American Sign Language has deep roots in Deaf culture and identity, yet its journey toward acceptance was anything but smooth. For decades, ASL was seen as a second-rate way to communicate, dismissed as a crude set of gestures rather than a full-fledged language.

Early Days of ASL and the Oralism Movement

The foundation of ASL was laid in 1817 with the establishment of the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut. Deaf students and educators worked together to create a rich language that drew from both French Sign Language and home signs, establishing the basis of ASL. Yet, the 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of the Oralism movement, which actively discouraged sign language and instead promoted speech and lip-reading as the “right” way to communicate. People like Alexander Graham Bell, who believed Deaf individuals would integrate better into society if they could speak, promoted Oralism, leading to a widespread suppression of ASL in schools.

This emphasis on Oralism was incredibly harmful. It forced Deaf individuals to operate in ways that didn’t suit their natural abilities, resulting in a generation of Deaf students who were denied the right to communicate fully and authentically. Astonishingly, for many years ASL was pushed out of classrooms, silencing Deaf individuals in the name of conformity.

ASL Gains Recognition as a Language

The tide finally began to turn in the 1960s, thanks in part to the work of linguist William Stokoe. Stokoe’s research proved that ASL was not just a collection of gestures but a fully developed language with its own syntax, grammar, and expressive power. This breakthrough helped shift perspectives, validating ASL as a legitimate language and encouraging educational and social spaces to adopt it more widely.

The Deaf community’s advocacy played a crucial role, too. They fought for ASL’s place in schools, workplaces, and public life, asserting that their language was both valid and essential to their identity. Legislative progress, like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, further strengthened this fight, requiring accommodations for Deaf individuals and setting a precedent for communication rights.

Non-Speakers and Letter Boards: A Modern Struggle for Acceptance

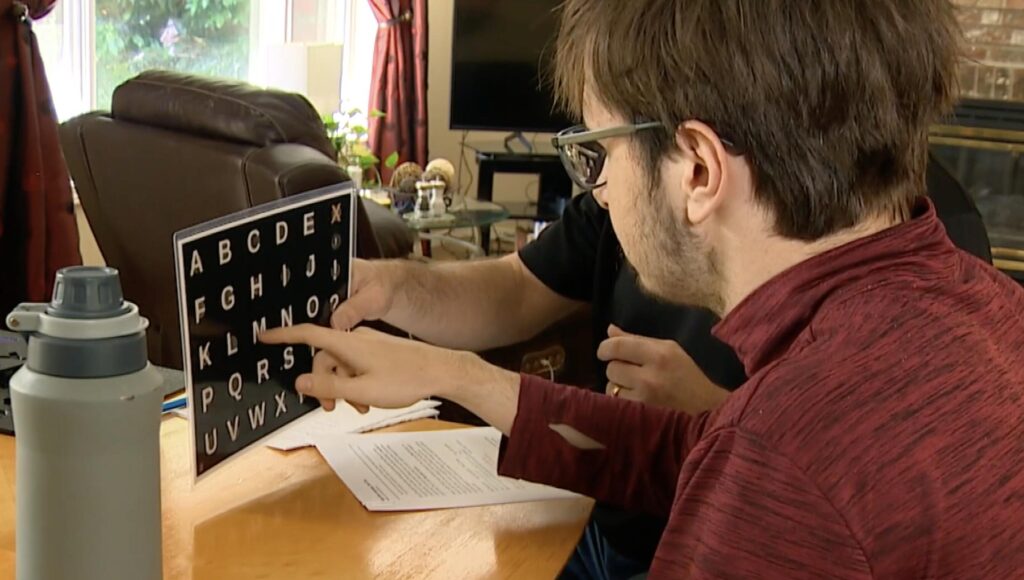

Today, non-speakers who rely on letter boards and Spelling methodologies such as Spelling to Communicate (S2C) are facing challenges that echo the journey ASL took. In many school districts across the United States, letter boards aren’t seen as legitimate tools for communication. Some teachers, administrators, and even therapists question their validity, often comparing them to outdated forms of “facilitated communication” without understanding how the methodology and letter boards work together.

Just as ASL was misunderstood and discouraged, letter boards are too often met with skepticism and, at times, outright rejection in our school districts. The fundamental issue here is the presumption of competence: the belief that non-speakers have their own thoughts, ideas, and abilities, even if they don’t express them through typical means.

Fighting Stigma and Misunderstanding in Today’s Classrooms

In the case of letter boards, critics often argue that the process involves too much influence from the communication partner. But this critique reflects a lack of understanding. The primary role of a communication partner isn’t to guide responses; rather, it’s to help with regulation—holding the board so the non-speaker can concentrate on typing rather than controlling every movement of their own body. For those unfamiliar with how complex and exhausting regulation can be for non-speakers, it’s too easy to dismiss this method as unreliable.

This resistance to letter boards mirrors the Oralism movement’s refusal to acknowledge the value of sign language. We’re witnessing a similar insistence that non-speakers should rely on more conventional communication methods, even if those methods are ineffective for them. By limiting the communication tools non-speakers can use, schools and institutions are silencing them just as ASL was silenced in the past.

Advocating for Acceptance and Understanding

Much like the Deaf community before them, non-speakers and their allies are pushing for change. Parents, practitioners, and communication advocates are standing up to challenge the biases and misconceptions that hold non-speakers back.

Today, we have dozens of stories from non-speakers who have not only achieved academic success but also explored creativity through writing songs, poetry, and even plays. New friendship groups and blogs written by non-speakers are springing up almost weekly, sharing experiences and perspectives in their own voices. This wave of self-expression is undeniable, and it continues to grow as more non-speakers gain access to various Spelling methodologies. These stories make it clear: these tools don’t just work—they are transforming lives and building communities.

Unlike the early days of ASL advocacy, we now have a robust and growing body of research confirming that non-speakers are indeed authoring their own messages. In fact, more than 100 peer-reviewed studies using diverse methodologies support this. A recent study out of the University of Virginia tracked both eye and hand movements to determine which occurs first. The findings showed that the eye moved to the letter before the finger followed, demonstrating the clear intention and capabilities of spellers. This research is powerful evidence of the authenticity and reliability of spelling as a communication method.

Unfortunately, many of the studies used to discredit spelling incorrectly lump it together with Facilitated Communication (FC). While related, FC and Spelling methodologies are very different. Spelling does not rely on physical touch to communicate, and many spellers type independently, requiring a communication partner only to assist with regulation. This distinction is crucial because it shifts the focus to what truly matters: supporting non-speakers in managing their bodies and environments so they can communicate autonomously.

Learning from ASL’s Journey

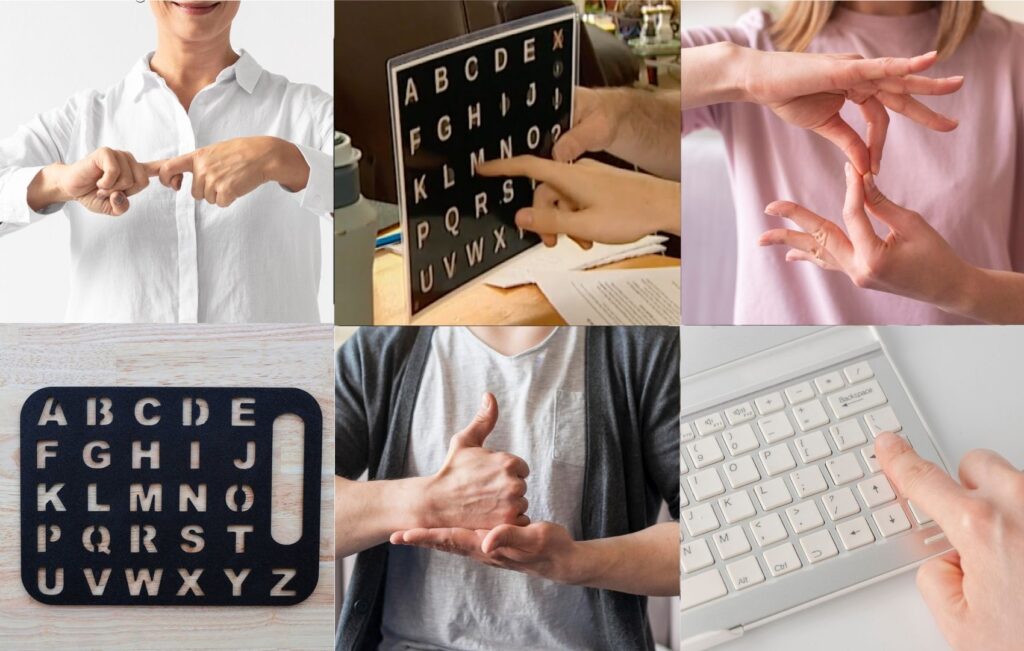

The history of ASL provides us with essential lessons. First and foremost, it reminds us of the importance of presuming competence, even when the ability to communicate appears unconventional. The Deaf community’s journey toward recognition was fueled by their insistence that they had a right to communicate in the way that suited them best. Non-speakers deserve the same respect, and their tools—whether letter boards, keyboards, or other adaptive technologies—should be recognized as valid.

The second lesson is that change requires community. The acceptance of ASL didn’t happen in isolation; it was achieved through the collective efforts of Deaf advocates, allies, and researchers. Likewise, non-speakers, their families, communication partners, and allies must work together, pushing back against institutional biases and misconceptions to create a world that’s ready to listen and understand.

Finally, while history teaches us that change can sometimes take a long time, non-speakers simply don’t have the luxury of waiting. Their voices deserve to be heard now. Anyone who works closely with Spellers sees the immediate, undeniable importance of communication and their clear ability to convey independent thoughts. For non-speakers, the ability to communicate isn’t a distant goal—it’s a present reality, one that deserves immediate acknowledgment and respect. Every day that their voices are sidelined is a day they’re denied the fundamental right to participate fully in their own lives.

Moving Forward

Non-speakers have a right to be understood on their own terms, just as Deaf individuals fought for the right to use ASL. By advocating for the legitimacy of letter boards, we’re not only advocating for a tool—we’re advocating for non-speakers’ fundamental right to express themselves. Just as ASL transformed the lives of Deaf individuals by giving them a way to communicate, letter boards and S2C have the power to unlock a world of thoughts, emotions, and dreams that non-speakers have been waiting to share.

As we continue to push for acceptance, let’s remember that what’s at stake here is more than just communication. This is about acknowledging the potential and humanity of people who deserve to be heard, respected, and valued. With every step forward, we move closer to a world where every voice—spoken, signed, or spelled—is recognized for the unique perspective it brings.