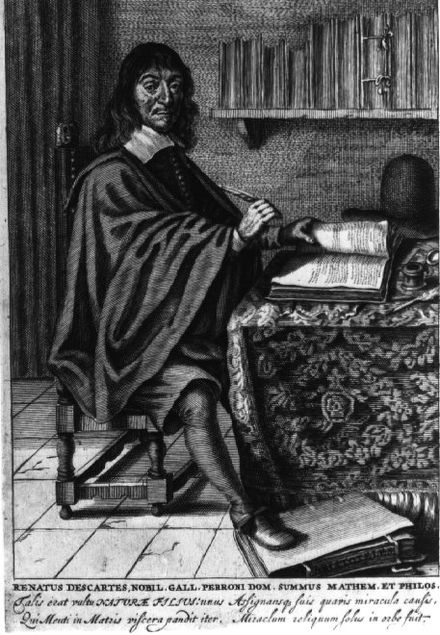

It’s a little ironic, isn’t it? Here we are in the 21st century, a time of rapid innovation, technological advancements, and (mostly) heightened awareness of diversity. Yet, a concept that lies at the very foundation of Enlightenment thinking—René Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am”—remains unacknowledged or misunderstood when it comes to certain groups of people, particularly non-speakers and many autistic individuals.

What Does “I Think, Therefore I Am” Mean?

Descartes argued that thought alone—the capacity to reason, reflect, and form ideas—was enough to affirm one’s existence and worth. During the Enlightenment, this idea was revolutionary, challenging centuries of dogma that tied human value to status, birthright, or religious devotion. And yet, despite the centuries of progress that followed, the simple truth Descartes championed still doesn’t seem to extend to everyone.

For non-speakers, this exclusion is all too familiar. Society often judges intelligence and capability through outward signs: speech, physical coordination, facial expressions. If you don’t fit those traditional communication molds, people jump to assumptions. But Stone, and so many others like him, defy these assumptions daily. They think. They create. They communicate – if and when given the tools and the chance.

The Challenge for Non-Speakers and Autistic Individuals

This reality hit home in an unexpected and profound way during Stone’s World History class this week. He and his teacher reviewed Descartes and his famous declaration about the nature of existence and thought. For Stone, the lesson wasn’t just academic; it was very personal. He told his teacher that he could relate to Descartes’ idea. “Our brain is all we need to prove our worth,” he said. “This was my life for so long.”

Think about that for a moment. Stone’s words cut to the heart of the struggle that non-speakers face every single day. Despite having a rich inner world filled with deep thinking, keen observations, and intense feelings, non-speakers are too often dismissed or devalued simply because they don’t communicate in ways most people expect. It’s as though the assumption is: “If you can’t speak, how can you prove that you’re truly capable of learning and thinking?” It’s a mindset that is as outdated as it is harmful.

Presuming Competence: A Path Toward Inclusion

This harmful assumption must be replaced with the principle of presuming competence. As advocates, parents, neighbors, friends and educators, we have to challenge ourselves and others to see beyond outdated perceptions. It’s not enough to say, “Well, maybe they’re capable.” We have to believe that they are capable from the start. We have to recognize that thought and intelligence don’t require the ability to form spoken words to exist.

I’ve had the privilege of witnessing this firsthand with Stone’s journey. For nearly 17 years, Stone’s thoughts and inner life were trapped inside his brain, misunderstood by a world that wasn’t able to hear him. That changed when he began using the Spelling to Communicate methodology in September 2022. Through this methodology, Stone was finally able to express himself—his ideas, hopes, fears, and humor!

Stone’s Journey of Empowerment with Spelling to Communicate

What Stone experienced in class is something I’m sure resonates with countless non-speakers around the world. When you’ve spent your life fighting to prove your intelligence, hearing someone articulate a philosophy like Descartes’—one that validates your entire inner world—is incredibly powerful. It’s a reminder that you have always been more than what society wrongly assumed about you. Your thoughts define you. And, as Descartes would say, that is enough.

But how do we move this philosophy from academic discourse into reality? We start by changing how we educate others. Schools, healthcare providers, and workplaces need to adopt inclusive practices that center on presuming competence. This also includes families and relatives. This means giving non-speakers access to communication methods that work for them, training professionals to recognize intelligence within non-speakers, and fostering environments where all forms of expression are respected.

It also requires advocacy on a broad scale. The more stories we share of non-speakers who excel academically, write poetry, compose music, or innovate in other fields, the harder it becomes for society to cling to its biases. These stories—of which there are now hundreds, if not thousands—are part of a growing movement that demands recognition and inclusion.

The Enlightenment taught us to value reason and the mind. It’s time we fully embrace that lesson by honoring the cognitive abilities of all individuals. Stone’s insight reminds us of what’s at stake. We have an opportunity to ensure that future generations won’t have to prove their worth over and over again simply because they communicate differently.

To those who might still be hesitant to accept this, I leave you with this thought: What if your greatest ideas, the very essence of your identity, were locked inside of you—visible only to you—because the world had decided that your voice didn’t matter? Wouldn’t you want someone to presume that you are more than what they see? Wouldn’t you want them to believe that you think, therefore you are?

As Descartes himself wrote: ‘Except our own thoughts, there is nothing absolutely in our power.’ It’s time we honor those thoughts, wherever they reside, and ensure that every voice has the opportunity to be heard.

Awesome article, Dave! I am enjoying following you and Stone’s journey.